Posthumous encounters

I do not look for the beginnings, nor do I find myself being adhered to any finite resolutions. I often start in the middle. The middle ground from which one speculates, wanders, and searches for the gaps, absences, and moments of rupture in the historical processes, institutional formations, and systems of power relations. Notes on Seeing Double combines field notes, site of a museum in the Hague, and a series of historical gatherings in Tehran to perform their respected histories vis-à-vis photographic memory and to animate the pace of recollecting them. The middle ground of the image was only exposed once the image was scaled up, cut, sutured, and pieced back together. The middle ground was somewhere in the midst of a crowd and among a multitude of unlikely historical actors whose imprints may be recalled through discontinued flashes—back and forward.

Image-corpse-shadow

As its own grave, the photograph is what exceeds the photograph within the photograph. It is what remains of what passes into history. It turns in on itself in order to survive, in order to withdraw into a space in which it might defer its decay, into an interior- the dosed-off space of writing itself. In order for a photograph to be a photograph, it must become the tomb that writes, that harbors its own death.

—Eduardo Cadava, Words Of Light: Theses On The Photography Of History, 1997

The “Image-corpse” relationship that Eduardo Cadava has so beautifully expanded upon is another middle ground from which I started this film. Notes on Seeing Double expands the purview of the dialectical image by writing with and through the shadows of death in photographs. In fact, it was only through a sudden and shocking encounter with a previously unrecognized shadow in a photograph that this film was conceived in the first place.

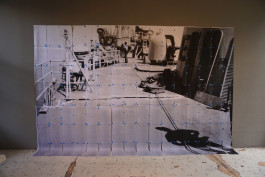

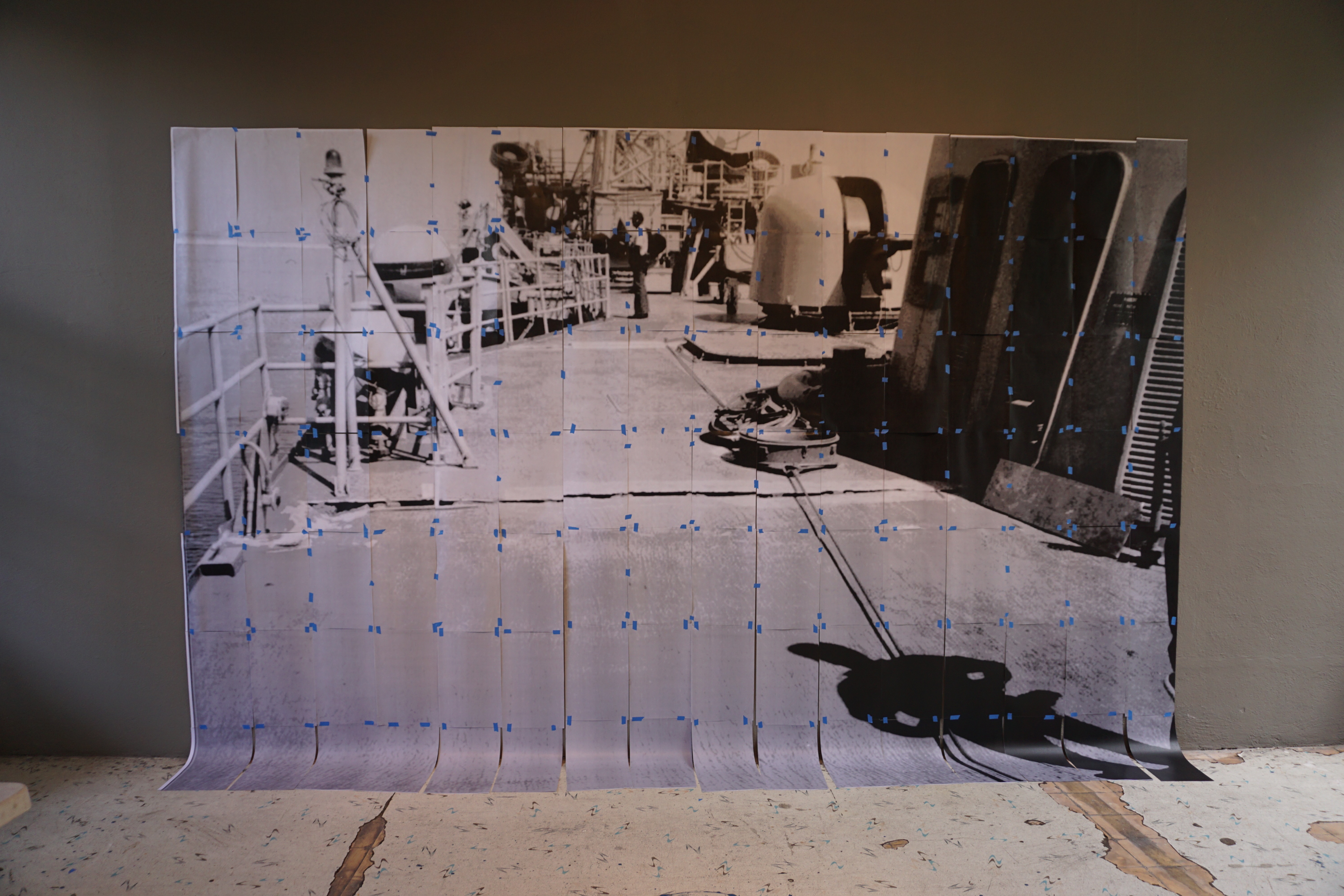

Stepping back, the enlarged photograph seems eerily unfamiliar. The photograph is taken on an American military ship in 1988 in the midst of the Tanker Wars (1984–1988). It was collected from the Library of Congress’ open access archive of the United States “Veteran History Project” which is an informal archival labyrinth of the United States military complex and its multitude of contemporary wars compiled through personal contributions of its former and current soldiers. The contents of this archive can be horrific, mundane, and accidental all at the same time. Audio files, photographs, notes, dates, names, places, video interviews, etc. Memorabilia to piece together a narrative as archivable, thus legible, if completely flawed.

I step back and recognize the shadow. It falls through from the right side corner of the image and diagonally cuts it. The photograph was supposed to be a mundane capture and the shadow was just simply another gradience of light on the navy ship’s deck, or so I thought. Once enlarged, the former gradience becomes a shadow, a witness to the photograph being taken, and active participant in the events during the Tanker Wars. Following Cadava, if the photograph is the allegory of our modernity, and the image-corpse relationship embodies the shadow within, isn’t the image-corpse-shadow dynamism the allegory of our contemporary history?

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation documentation, 2017

Assemblies

Why this desire for a body archive, for an assembly of history’s traces deposited in me?

—Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You, 2018

In her book “No Archive Will Restore You,” Julietta Singh poses many compelling questions about what constitutes the bodily archive for queer bodies. In Singh’s self-reflective queries lies the necessity to expand what an archive could be; collection of images, site of a monument, discards and accumulations, struggles and sufferings. The assembly of historical traces comes with sites and acts of deposition. Their assemblage—read archive—also needs to be critically unpacked, whether through use of spoken word or image making.

Photographic archives entail a form of conservation drive as much as they imply the conditions of destruction and death. There would be no archival desire without the radical finitude and without the possibility of forgetfulness. The desire for accumulation of memories is due to the possibility of destruction, finitude, and death of the very same memories. This internal contradiction of the archives reverberates with the event of photography, which embodies this dialectical tension very well; it is a simultaneous reduction and maximization of distance. Photography seems to determine our conception of reality; it also distances us from the already distanced reality it presents to us.

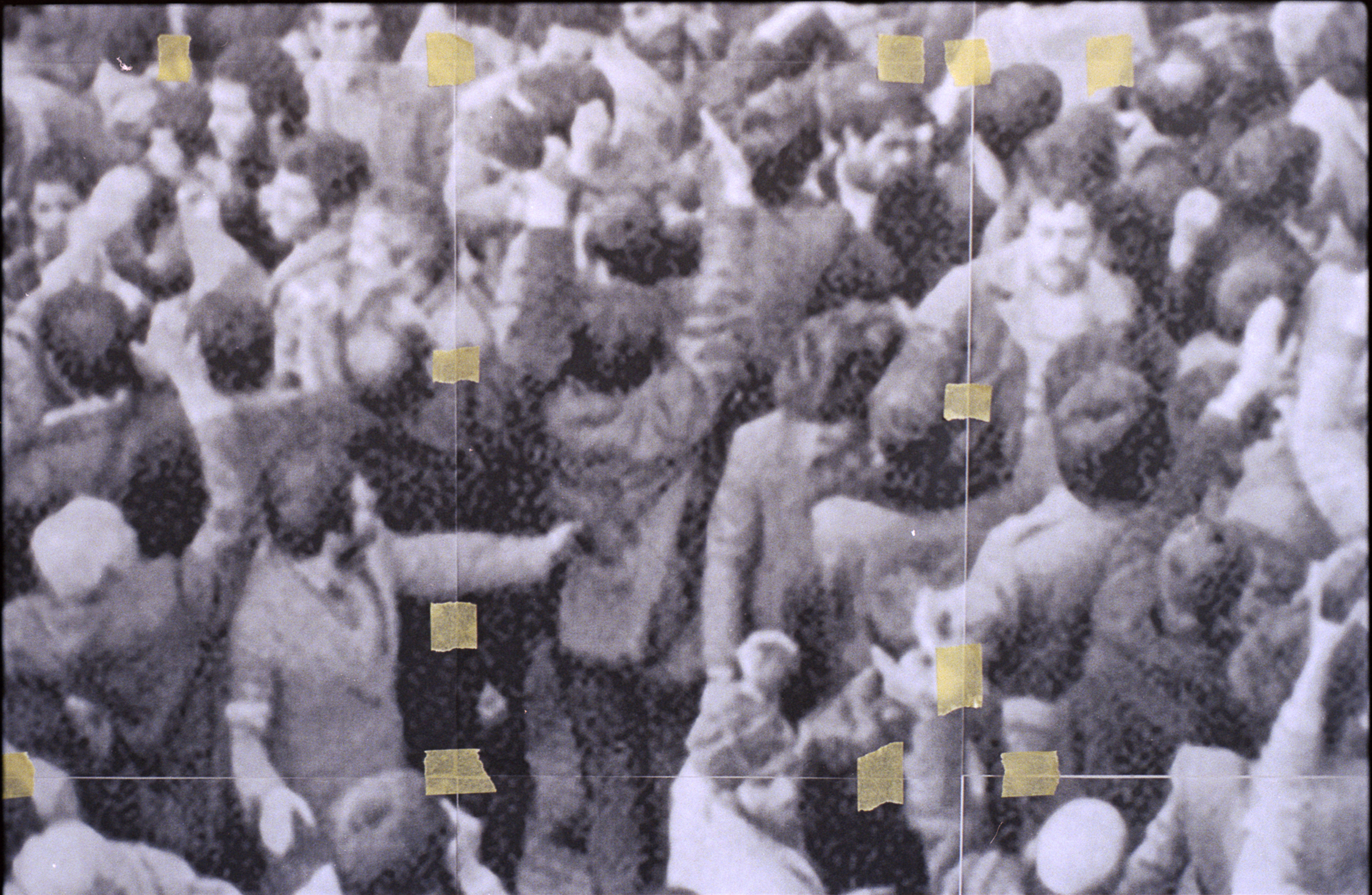

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation/process, Digitized 35mm Color Photograph,, 2018

Uttering Images

The problem is that cruel images vary in intent. Traditionally cruel images would point to tragedy. But increasingly, the image is part of the tragedy, or the tragedy itself—because cruel images have the potential to be easily co-opted. They can so perfectly render flat the possibility of political reimagination and organization precisely because they are used as proof of the outcome of the audacity to imagine. And that is the very problem, because the issue is no longer about “compassion fatigue,” “voyeurism,” or “pornography,” but that the cruel image’s very two-dimensional plane is the weapon.

—Oraib Toukan, Cruel Images in e-flux journal, 2019

Can we still sufficiently use a keyword such as representation to critically discuss the role of images and their capacity to incite meaning and feeling? Where does an image take us in our contemporary moment? Which elements in an image offer enough representative qualities to be placed vis-à-vis material and ideological structures in the world around us?

Oraib Toukan intentionally entangles the two old pals of representation; image and language to outline the cruelty and insufficiency of the former, the muteness of the latter, and the leakage between the two. In her essay “Cruel Images,” Toukan connects the semantics of certain Arabic words to the shifting mechanics of gaze in the age of digital circulation of images of suffering online. For Toukan, the relationship between an unspeakable image of pain experienced digitally and the deception embedded in acts of translation through language should at least lead to a critical assessment of relational space of politics between the photographed person, photographer, and spectator.

Following Toukan and her concise marriage of semantics and operational mode of images, I approached one of the most seminal keywords in photographic theory—representation—through the avenue of Persian literature and linguistics and the usages of Temsaal | لاثمت. The fixated sets of binaries in representation—i.e., inside/outside, photographer/photographed, fiction/reality, to name a few—within the Western hermeneutics are in fact more imbued with trickery and mysticism when it comes to the equivalent usage of the term in Persian literature and poetry.

In Notes on Seeing Double, Temsaal | لاثمت became the point of departure to address the representation of historical progress through visual and photographic archives through which I aimed to critically unpack the relational space of politics in photographic archives. Temsaal | لاثمت is a longing for a face to come, meanwhile, it may also trick the eye in believing that the image has already appeared. The brilliance of Temsaal | لاثمت lies in tricking the mind to ignore what it sees and put aside the evidentiary status of the act of seeing; representation often fails, you might as well trick representation itself all together.

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation/process, Digitized 35mm Color Photograph,, 2018

Posthumous encounters

I do not look for the beginnings, nor do I find myself being adhered to any finite resolutions. I often start in the middle. The middle ground from which one speculates, wanders, and searches for the gaps, absences, and moments of rupture in the historical processes, institutional formations, and systems of power relations. Notes on Seeing Double combines field notes, site of a museum in the Hague, and a series of historical gatherings in Tehran to perform their respected histories vis-à-vis photographic memory and to animate the pace of recollecting them. The middle ground of the image was only exposed once the image was scaled up, cut, sutured, and pieced back together. The middle ground was somewhere in the midst of a crowd and among a multitude of unlikely historical actors whose imprints may be recalled through discontinued flashes—back and forward.

Image-corpse-shadow

As its own grave, the photograph is what exceeds the photograph within the photograph. It is what remains of what passes into history. It turns in on itself in order to survive, in order to withdraw into a space in which it might defer its decay, into an interior- the dosed-off space of writing itself. In order for a photograph to be a photograph, it must become the tomb that writes, that harbors its own death.

—Eduardo Cadava, Words Of Light: Theses On The Photography Of History, 1997

The “Image-corpse” relationship that Eduardo Cadava has so beautifully expanded upon is another middle ground from which I started this film. Notes on Seeing Double expands the purview of the dialectical image by writing with and through the shadows of death in photographs. In fact, it was only through a sudden and shocking encounter with a previously unrecognized shadow in a photograph that this film was conceived in the first place.

Stepping back, the enlarged photograph seems eerily unfamiliar. The photograph is taken on an American military ship in 1988 in the midst of the Tanker Wars (1984–1988). It was collected from the Library of Congress’ open access archive of the United States “Veteran History Project” which is an informal archival labyrinth of the United States military complex and its multitude of contemporary wars compiled through personal contributions of its former and current soldiers. The contents of this archive can be horrific, mundane, and accidental all at the same time. Audio files, photographs, notes, dates, names, places, video interviews, etc. Memorabilia to piece together a narrative as archivable, thus legible, if completely flawed. I step back and recognize the shadow. It falls through from the right side corner of the image and diagonally cuts it. The photograph was supposed to be a mundane capture and the shadow was just simply another gradience of light on the navy ship’s deck, or so I thought. Once enlarged, the former gradience becomes a shadow, a witness to the photograph being taken, and active participant in the events during the Tanker Wars. Following Cadava, if the photograph is the allegory of our modernity, and the image-corpse relationship embodies the shadow within, isn’t the image-corpse-shadow dynamism the allegory of our contemporary history?

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation documentation, 2017

Assemblies

Why this desire for a body archive, for an assembly of history’s traces deposited in me?

—Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You, 2018

In her book “No Archive Will Restore You,” Julietta Singh poses many compelling questions about what constitutes the bodily archive for queer bodies. In Singh’s self-reflective queries lies the necessity to expand what an archive could be; collection of images, site of a monument, discards and accumulations, struggles and sufferings. The assembly of historical traces comes with sites and acts of deposition. Their assemblage—read archive—also needs to be critically unpacked, whether through use of spoken word or image making. Photographic archives entail a form of conservation drive as much as they imply the conditions of destruction and death. There would be no archival desire without the radical finitude and without the possibility of forgetfulness. The desire for accumulation of memories is due to the possibility of destruction, finitude, and death of the very same memories. This internal contradiction of the archives reverberates with the event of photography, which embodies this dialectical tension very well; it is a simultaneous reduction and maximization of distance. Photography seems to determine our conception of reality; it also distances us from the already distanced reality it presents to us.

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation/process, Digitized 35mm Color Photograph, 2018

Uttering Images

The problem is that cruel images vary in intent. Traditionally cruel images would point to tragedy. But increasingly, the image is part of the tragedy, or the tragedy itself—because cruel images have the potential to be easily co-opted. They can so perfectly render flat the possibility of political reimagination and organization precisely because they are used as proof of the outcome of the audacity to imagine. And that is the very problem, because the issue is no longer about “compassion fatigue,” “voyeurism,” or “pornography,” but that the cruel image’s very two-dimensional plane is the weapon.

—Oraib Toukan, Cruel Images in e-flux journal, 2019

Can we still sufficiently use a keyword such as representation to critically discuss the role of images and their capacity to incite meaning and feeling? Where does an image take us in our contemporary moment? Which elements in an image offer enough representative qualities to be placed vis-à-vis material and ideological structures in the world around us? Oraib Toukan intentionally entangles the two old pals of representation; image and language to outline the cruelty and insufficiency of the former, the muteness of the latter, and the leakage between the two. In her essay “Cruel Images,” Toukan connects the semantics of certain Arabic words to the shifting mechanics of gaze in the age of digital circulation of images of suffering online. For Toukan, the relationship between an unspeakable image of pain experienced digitally and the deception embedded in acts of translation through language should at least lead to a critical assessment of relational space of politics between the photographed person, photographer, and spectator.

Following Toukan and her concise marriage of semantics and operational mode of images, I approached one of the most seminal keywords in photographic theory—representation—through the avenue of Persian literature and linguistics and the usages of Temsaal | لاثمت. The fixated sets of binaries in representation—i.e., inside/outside, photographer/photographed, fiction/reality, to name a few—within the Western hermeneutics are in fact more imbued with trickery and mysticism when it comes to the equivalent usage of the term in Persian literature and poetry. In Notes on Seeing Double, Temsaal | لاثمت became the point of departure to address the representation of historical progress through visual and photographic archives through which I aimed to critically unpack the relational space of politics in photographic archives. Temsaal | لاثمت is a longing for a face to come, meanwhile, it may also trick the eye in believing that the image has already appeared. The brilliance of Temsaal | لاثمت lies in tricking the mind to ignore what it sees and put aside the evidentiary status of the act of seeing; representation often fails, you might as well trick representation itself all together.

—Sanaz Sohrabi

Sanaz Sohrabi, Studio installation/process, Digitized 35mm Color Photograph, 2018